Our last trip through Croatia was 17 years ago.

At that point, just 10 years after its devastating but triumphant War of Independence from the former Yugoslavia, Croatia was still finding its footing.

Many roads were nearly Third World; the buildings pockmarked from bullets and missiles; the memorials to the war dead front and center; and the people, let’s just say, not overly friendly. A wedding party arrived bedecked in patriotic flags and sparklers and the wedding party singing the national anthem.

Now, 27 years on, Croatia’s topography is as gorgeous as ever: spectacular coastline and islands, inland green mountains. It’s historical settlements breathtaking.

But the infrastructure improvement is what we found most stunning.

Beautiful modern highways run the country’s length. And now there’s no need to pass through Bosnia and Herzegovina to reach the southern noncontiguous portion of Croatia, which includes Dubrovnik – or to wait in long lines at two international custom checkpoints to do so as we did.

The 1.5-mile-long span also includes more than 20 miles of access roads, tunnels, bridges and viaducts.

The bridge was symbolic of our overall new impression of the country: Croatia is back and better than before.

Tourists have quickly learned it’s equally as dazzling as Italy and Greece, in some cases more so. (Game of Thrones, shot around Dubrovnik’s old town, is largely to blame and the city is embracing it.) It’s also just a short jaunt if you also want to see those other regions. Croatia Airlines increased European flights this summer and will increase further in the summer of 2023.

Croatia’s awash in astonishingly preserved ancient architecture such as Diocletian’s Palace in Split and the walls, towers and fortress of Dubrovnik. If the crowds of Dubrovnik deter you, there are many other smaller towns and cities such as Pula, Trogir and Ston to discover.

But passing on the equally remarkable sites on its islands off the coast, such as Korcula’s walled city, would be a mistake. The best way to see these islands is by private charter, in our case friends who are certified captains and could command a private yacht.

Staying in the oldest portions of the cities is highly recommended and we did so. In Split, near to Diocletian’s Palace. In Dubrovnik, on the main thoroughfare in the heart of the walled city, in a house reconstructed after the 16th century earthquake.

But while the outside roadway infrastructure has improved so much, travelers should expect that personal travel around the medieval cities has stayed locked in time.

If you want to stay amidst the most historic areas, expect that it won’t be handicap accessible. There will be lots of stone stairs and uneven and slippery stone walkways.

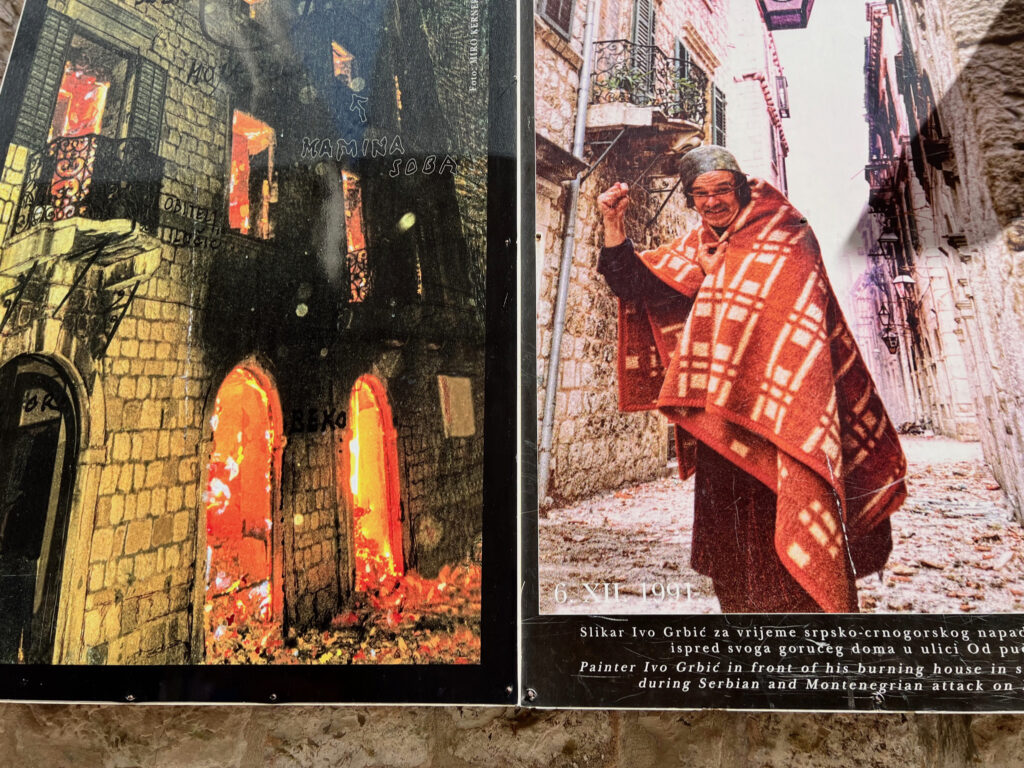

And, if you look closely, there are still reminders of Croatia’s not-too-distant turbulent past.

Outside of Split, on your way to visit prominent modern sculptor Ivan Mestrovic’s gallery and chapel, which contains much of his astounding work, you’re likely to encounter more of the “unfriendly” types we’d encountered in the past.

Our hotel clerk in historic old town Split alluded to the bad feelings that remain. She nodded to a young man who would help us with our luggage. “He’s a nice Serbian,” she said.

But encountering a Serbian at all in Croatia is growing less likely. Hundreds of thousands left after the war, and the most recent census in 2021, showed their numbers continue to significantly drop – now to less than 3% of the country’s population and down 30% from the previous census a decade before.

Our clerk was just one indicator that their social stigma is still at play.

And in Dubrovnik, a city that was the focal point of a siege during the war, the Museum of Franciscan Monastery, a hole in the wall made by a Serbian missile remains, now covered with plexiglass and labeled.

But the memorial displays have moved to the side streets.